Sound Presets—The Lifeblood of Any Synthesizer

The History and Significance of Sound Expansion

The synthesizer was originally conceived as an instrument that musicians could use to create sounds free of any restriction, and while this was of course a highly valued ability, once it became possible to store the sounds you had crafted, the sounds themselves took on value. And if you dreamed of playing exactly the same sounds as your favorite synthesizer musicians, a sound library could make that a reality.

Straight out of the box, a new synthesizer already came with a host of built-in sounds, which were often referred to as the “factory presets,” or collectively, the “preset library.” While instrument designers and developers did their utmost to create interesting sounds that showcased the unique abilities of each particular synthesizer, early on there was a limit to how many of them could actually be stored on board. In the professional recording studio, meanwhile, musicians and operators would regularly tweak these presets to better match the music, often elevating them to a key role that made the song really sound like a hit.

Cartridges Allowing Presets to be Also Stored Off-board

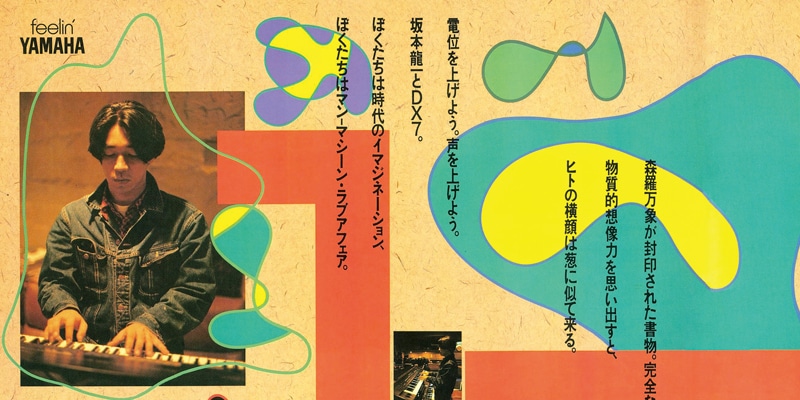

One of the reasons often given for theDX7’s explosion in popularity in the global music scene was the way in which its preset library could be expanded. While some earlier analog synthesizers did also allow sounds to be stored and recalled at the touch of a button, these sounds were invariably saved within the instrument’s internal memory. The FM tone generator in the Yamaha DX7 was, of course, digital, and so was its preset data. This meant that sounds—or voices—created by the user could be stored on digital memory cartridges that were plugged into special slots. As such, it became incredibly easy for users to save a greater number of sounds and work with a much more diverse range of voices. The instrument’s internal memory could hold 32 different presets, but each expansion cartridge—two of which could be plugged in at any time—could store another 64.

This meant that a new DX7 offered a total of 160 voices. The ROM (read-only memory) in these bundled cartridges did not support overwriting of presets, although they could be read into the synthesizer ‘s memory and edited; however, we also sold RAM (random-access memory) cartridges, and users could freely store their own voices on them, pull them out, and carry them around in their pocket.

New Applications and Commercial Activity Brought about by the Cartridge

Plug-in memory cartridges were a catalyst for the DX7 being used in a range of new ways, not the least of which was as the default synthesizer for the music industry. In a wide range of popular-music genres, the synthesizer had started to become a familiar face in studio and on stage, but if you wanted to use the same sounds in both places, the synthesizer containing them would need to be physically ferried back and forth. And, of course, this was not even an option when the live venue and recording studio were quite far apart. In this case, there was no alternative but to compromise and perform on a backup synthesizer with different sounds. With the arrival of the cartridge, however, sounds could be freely carried around separately from the synthesizer. To use the exact same sounds on stage, the performer just had to borrow a DX7 from an instrument rental company close to the venue and plug in the right cartridge. While already popular with music professionals, this capability also helped the DX7 to make inroads into rehearsal studios and other areas of the amateur market. And this was not limited to Japan: in countries all over the world, the desire to have a DX7 on hand wherever synthesizers were played contributed greatly to sales.

Thanks to the ROM cartridge, we also saw a vibrant new business spring up around synthesizer voices. Amateur musicians have always wanted to play exactly the same sounds as those used by their favorite artists for recording and live performance, and by simply buying a cartridge containing these sounds, their wish could now be granted.

With the DX7 becoming firmly engrained as the industry’s standard synthesizer, more amateurs started choosing this instrument as the first step to maybe becoming a pro, which further invigorated the market for voice cartridges. Sales of hardware in the form of the synthesizer itself and software in the form of presets thus had a multiplier effect, further boosting the popularity of the DX7.

Floppy Disks Greatly Expand Storage Space

With the arrival of the 3.5-inch floppy disk at the start of the eighties, digital storage media could now hold much more data than ever before.

Whereas 4 KB was required for the 32-sound preset library on board the DX7, the 2DD variety of 3.5-inch floppy disk offered up to 720 KB.

Simple math tells us that just one of these disks had 180 times the storage space of the entire synthesizer. With the DX7IIFD of 1986 featuring a 3.5-inch floppy disk drive, users were no longer limited to RAM cartridges for off-board storage of voice data. What’s more, floppy disks could also be used to store voice data from models not equipped with RAM or ROM cartridges, as well as Yamaha QX Series sequence data and the like. And with widespread adoption helping to drive down the price of this general-purpose media, the number of synthesizers coming with floppy-disk drives also grew.

Following the release of tone generators such as Yamaha’s AWM2, synthesizer programmers started to use samples more and more in their sound-creation activities. No longer was it sufficient to just store voice parameters: this paradigm shift in sound sculpting required that the sample data on which each voice was built also be stored, often together with the corresponding voice parameters. Samples take up much more space in memory than voice parameters. For example, just one second of 16-bit mono audio recorded at 44.1 kHz requires around 85 KB. Further compounding the issue was the use of multi-sampling, where a single voice could use many different samples assigned to different zones of the keyboard and velocity ranges.

Sticking with our example of one second of audio, if the user had different samples for eight keyboard zones and also eight velocity ranges, we are talking about more than 5 MB of storage space for just one voice. It would simply be impossible to store this data on the 2DD 3.5-inch floppy disks in use in the early nineties. As such, programmers learned to become frugal in their sound creation by keeping samples as short as possible and limiting their usage of different keyboard zones and velocity ranges.

Synthesizers that could work with sampled waveforms also needed considerable on-board memory to house them, so we released memory expansion boards for our SY Series and other similar instruments.

As the synthesizer started to be called on more and more to stand in for acoustic instruments in the recording process, demand grew for more realistic voices, and the focus of producers turned towards the dedicated sampler. And when the industry coalesced around a series of these instruments from another manufacturer, third-party vendors started to market a wide variety of compatible sample libraries. As such, users became even more interested in the potential of the sampler as a serious instrument. Of course, the market for sound expansion for synthesizers did not simply contract and shift to samplers; Yamaha’s sound expansion business also faced another, different struggle, which was the lack of compatibility with supplied media, as well as compatibility between different models. For example, voices for the EOS B200 came on ROM cards, while those for the V50—which used the same FM tone generator—were sold on floppy disks. Another example can be found in the SY Series, where minor differences in voice parameters made communalization and standardization impossible, so that separate libraries had to be sold for the SY77 and SY55, and users had to purchase sound expansions for each model.

Conversely, other companies that had been quicker to release synthesizers based on PCM waveforms created shared formats for sound expansion cards that integrated memory expansions and waveform libraries, and brought to market products that allowed users to use cards they had purchased in later models as-is. Together with sampler waveform libraries, these found acceptance in the marketplace, so that in the 1990s Yamaha’s strategy of voice libraries was lagging behind.

Storage-media Transformation and Falling Memory Costs

The worldwide popularity of Microsoft Windows 95/98 in the latter half of the nineties drove an increase in demand for PC memory, which in turn led to the prices of this type of memory dropping year on year. New forms of digital storage media—such as flash and USB memory—also appeared on the scene, redefining the ways in which sample data and voice parameters were being saved. It had been normal in the past for the price of a synthesizer to increase dramatically when it was given more on-board memory, so users understandably preferred external media for the distribution and storage of voice data.

However, these major reductions in the price of memory ushered in an era where new synthesizer—including Yamaha AWM2 models—would normally include large volumes of on-board samples and other voice data. This trend can be easily seen by comparing the MOTIF of 2001 and the MOTIF XF of 2010. Whereas the former came with 384 normal-voice presets and 1,309 waveforms in sample memory, the latter boasted 1,024 such presets and 3,977 waveforms.

The voice and sample expansion libraries being sold at the time were usually categorized into musical genres such as rock, pop, and jazz, and instrument genres such as brass, strings, and percussion. It became very easy for synthesizer owners to just go out and buy libraries containing the voices they needed, but when they ended up with as many as four thousand of them on board, searching became a problem. In comes Category Search—a Yamaha function that is still in use to this day.

The need for this particular function is, however, clear evidence that the landscape had changed: the challenge was no longer to constantly add new voices by creating them yourself or buying more, but to reliably find the right ones.

The Network Era and Preset Libraries

Further significant change came to the world of voice data post 2010 with the smartphone becoming ubiquitous and mobile network speeds skyrocketing. Huge blocks of data could now be exchanged over the Internet in an instant, and voice data obtained over a network from synthesizers at far distant locations could very easily be copied onto USB memory and loaded into your own instrument. Adaptors that bestowed synthesizer USB and MIDI ports with wireless MIDI functionality also went on sale, and wireless connection between synthesizers and smartphones became a reality. Leveraging these capabilities, Yamaha released the app “Soundmondo” so that countless creators all over the world could easily share their sounds with one another. Synthesizer presets—the very lifeblood of the instrument—had now truly transcended the boundary of on-board memory capacity, and users could tap into an infinite supply of voice data spread out all over the world.

An Approach to Promoting the Latest Hardware Synthesizers

In the era of the DX7, voice expansion systems were intended to supplement the onboard memory of a synthesizer, with each one offered as a separate library for each model sold at the time. However, synthesizers from the MOTIF onwards have been designed to maintain forward compatibility with models released in later years, allowing players to use the latest synthesizers to play their favorite voices created on previous models.

Although data from the MONTAGE M is saved with .Y2A (all backups), .Y2u (user area only), and .Y2L (library files) file extensions, this instrument can load files from the MOTIF XS (.X0A, .X0V, .X0G, .X0W), MOTIF XF (.X3A, .X3V, .X3G, .X3W), MOXF (.X6A, .X6V, .X6G, .X6W), MONTAGE (.X7A, .X7U, .X7L), MODX, and MODX+ (.X8A, .X8U, .X8L). The latest hardware synthesizers feature a slew of updates such as improved keyboard mechanisms and D/A converters, and compatibility with MIDI2, and offer users the advantage of being able to leverage these as well as use voice assets from past instruments.

Additionally, Yamaha offers the “FM Converter” web app that can convert voice files from instruments such as the DX7, DX7II, and TX802 into files that can be used on FM tone generator-equipped synthesizers from the MONTAGE onwards, giving users access to voices from more than 40 years ago. Moreover, a dedicated Yamaha version of the third-party “SampleRobot” application, “SampleRobot Pro MONTAGE Edition” has been released, and is available for use free of charge to purchasers of applicable products. “SampleRobot Pro MONTAGE Edition” automatically samples sound from any MIDI-compatible synthesizer (including analog synthesizers) and transforms them into voice files, making it easy to convert sound from these instruments into AWM2 voice files for use on the MONTAGE, MODX, MODX+, and MONTAGE M.

Efforts such as these constitute an important approach to the life of a synthesizer, offering users the reassurance that they will be able to use the voice assets they have created in future even though they may have used a range of instruments to create them at different times.

YRM-13 Voicing Program for the DX7

One of the great things about digital synthesizer s is that their voice parameters are represented as discrete values. The DX7 had digitized parameters right from the start, and the ability to exchange them with other devices via the MIDI standard was at that time ground-breaking.

This paved the way for Yamaha to release the YRM-13 voice editor application for the DX7. This application ran on the Yamaha CX5—a PC based on the standardized MSX architecture and one of the fruits of our efforts to build up our own production of semiconductors in the eighties.

No-one had invented anything like USB ports yet, so the CX5 first needed to be fitted with a MIDI expansion module, and then synthesizer and PC could be connected using MIDI cables. Prior to this, DX7 voice parameters could only be accessed one at a time as a number on the instrument’s LCD, but as shown, the user could now simultaneously edit many parameters together in a graphical environment displayed on the connected TV monitor. In this sense, the YRM-13 voice editor was truly pioneering. In the years that followed, as MIDI sequencing software for the Apple Mac saw widespread adoption, voice editors were also released for this operating system and became immensely popular. Alas, our DX7 editor running on the CX5 did not therefore become the go-to standard application for professional users, but we like to think that the technical knowhow exemplified by this breakthrough hardware/software integration lives on to this day in our development of new synthesizer.