Japanese Pop Music and Yamaha Synthesizers

In 1983, the Yamaha DX7 emerged into a Japanese pop industry that was being massively reshaped by the spread of MIDI. With the synthesizer now encroaching on the time-honored band format of drums, bass, guitar, and piano, and what’s more, the evolution of new studio techniques such as playing to a synthesizer track, a realignment was underway in both the sound and technology of Japanese pop. Keyboardists who had only previously needed to master piano and organ struggled to get to grips with sound creation and sequencing, and a new breed of musician that ultimately came to be known as synthesizer operators or synthesists was called for. In order to better understand the effect that Yamaha synthesizers had during this period of change, we spoke to four such synthesizer programmers who have been active in the vanguard of Japanese pop since the eighties and continue to work with prominent artists to this day.

We were delighted to welcome Nobuhiko Nakayama (NN), Shigeaki Hashimoto (SH), Yoshinori Kadoya (YK), and Yasushi Mohri (YM)—all of whom have worked with household-name Japanese pop artists. We started the discussion by asking how they found their way into the world of synthesizer programming.

Q: Nobuhiko, what was the initial spark for your career with synths?

NN: It happened in 1980, when I started working at a musical-instrument rental company called Sun Lease, which managed musical instruments for Yamaha Music Foundation. One day, I discovered a Moog modular synthesizer in the instrument store, and I got so absorbed with twiddling the knobs and manipulating sound that my boss decided on the spot to put me in charge of synths as well. I was a roadie for a leading synthesizer operator for a while, but he was always late (laughs), so one day, the producer asked me to step in, and that’s where it all started.

Info was pretty hard to come by back then, and particularly with synths from overseas, I remember staring at the English manual for hours between recording sessions until somehow, I understood.

Q: Yoshinori, you also got into the business as a roadie, didn’t you?

YK: I joined Top, which was run by Takeshi Fujii, in 1988, and they sent me out to work at various studios. I got lucky one day at Yuko Hara’s place about six months later when Takeshi Kobayashi invited me to help him with pre-production for Taeko Onuki. I was put to work on the Vision sequencer that had just been released for the Mac, but it caused so much trouble and nearly drove me to the point of jumping ship.

Somehow, I managed to get it to behave, though. That led directly to an opportunity to work on music by Southern All Stars, and I’m still working with them.

Q: I believe you got into the industry in the nineties, Yasushi...

YM: That’s right. I had originally worked with percussion instruments, but in 1995, I heard from someone at a school I was going to that the arranger Satoshi Kadokura was looking for a runner. I was curious to see what a studio looked like, so I took the job. It was quite an emotional moment when I heard the sounds of all kinds of instruments, including drums, emanating from a massive bank of gear and realized that synthesizers were not just about bleeps and bloops. After that, I immersed myself in synthesizer for percussion tracks, aiming to do as much as possible with this one instrument. I asked the company to let me become a synthesizer programmer, and they agreed. In that role, though, I couldn’t just program drum sequences and had to learn how to also create sounds on a synth—that was quite the challenge.

Q: And how did you get your start, Shigeaki?

SH: I’d played in bands since high school, but amateur bands don’t have their own PA guy, so we had to mix ourselves. That got me to thinking that audio engineering could be an interesting career, so I signed up for a sound reinforcement course at a vocational college. Once that finished, I started looking for an engineering job and went for an interview at a studio called Smile Garage. But when a synthesizer programmer there heard that I played keyboards in a band, he asked if I could join his section instead, and that’s how I ended up getting into synthesizers. For the first four or five years, I learned a lot working with leading synthesizer programmers Itaru Sakoda and Tetsuo Ishikawa, but they finally started letting me handle things for myself and I eventually went out on my own. Later on, the president of Smile Group, where I currently work, told me to go and help Tatsuro Yamashita because he was taking a bit too long to finish his album. That was a big break for me, because even now, I still help on projects for Tatsuro and other artists like Mariya Takeuchi.

Q: Can you tell us about any notable involvements you had with Yamaha synthesizers over the course of your careers?

NN: In the eighties, the Yamaha Popular Song Contest and the World Popular Song Festival—also held by Yamaha—had a kind of unwritten rule that strongly encouraged participating artists to play Yamaha instruments. This meant that all sounds originally produced on synths from other companies had to be reprogrammed on Yamaha synths, and I remember spending quite a lot of time working on Yamahas to this end. I was also involved in making Yamaha genuine voice ROMs for the DX7.

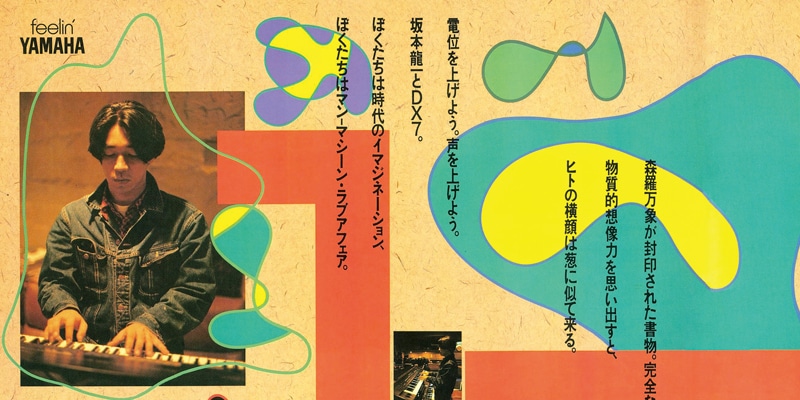

YM: The SY Series was already out by the time I started work, and up until the MOTIF was released, every new synthesizer either had completely different specs from the previous models or an altogether different way of producing sound. Whenever we got a new one, I remember a mad rush to read the manual and learn how to use it. No more so than when working with Ryuichi Sakamoto because he kept sending me the latest Yamaha models (laughs).

YK: I always had a TX802 with me. Yamaha synths have an excellent reputation for clear, crisp tones, although that can make them stand out a bit too much in the mix... I definitely used Yamahas a lot for electric piano sounds, and also for bass.

NN: You could actually pull reference cards (Note 1) right out from the bottom of the TX802 – how analog is that!?

YM: Yeah. I thought that was a really good idea, though.

SH: The TX816 had something similar and I was always grabbing it to check stuff.

YM: Does anyone remember a gizmo called the breath controller? I thought it was an amazing input device, but you can’t get them new any more, right? I’ve recently been thinking about using one, so was on the look out for something second-hand, but it would have been in someone else’s mouth... so, yeah, I’d be a little hesitant (laughs).

NN: You need pretty good lungs for that one, alright. I’d seen foreign artists using the breath controller and thought it looked pretty cool, but when I finally got to try one for myself, it wasn’t as easy as it looked.

Note 1:

Plastic reference cards containing the same details of algorithms and parameters that were printed onto the DX7’s top panel could be extracted from the bottom of the TX802 and similar synths. Back in the day, when sculpting tones armed only with buttons and a text display, synthesizer programmers needed to have this indispensable information at their fingertips.

Q: So is it true to say that—when it comes to synths—the Yamaha brand name has a very strong association with FM?

SH: The first synthesizer I ever played was the DX7. It really was a transformative instrument with its polyphonic capabilities and ability to both store and name sounds, all at a very reasonable price. Even when synths back then let you store patches, you could only assign them to buttons, so you had to put strips of tape on the front panel with the names of the sounds written on them or you’d forget which was which. But with the DX7, you could actually name them in memory, so for my live performances, I named my patches based on the song they were from.

I still use the TX816 because its FM sounds are clear and solid, and they lose none of their quality when reverb, chorus, and other similar effects are added. Tatsuro likes recording synths in mono, and he really loves FM tone generators because, unlike recent synths that spread out to fill the entire audio spectrum, you can use them to make sounds that hit a specific range with pinpoint accuracy.

NN: The DX7 has a totally different personality from anything that came before. No previous synthesizer had been able to make such convincing piano sounds—especially electric pianos. From the point of view of its tonal capabilities and polyphony, it was a real innovation. The DX7 quickly became the go-to synthesizer for electric piano sounds, and it also came to epitomize urban contemporary music.

YM: The DX7 has a really good keyboard, too. I got the impression that this instrument was absolutely not a toy, and I wonder if that came from pairing such a good keyboard with frequency modulation. There is a real sense of oneness when performing with your own sounds on the DX7, almost as if they know what you are trying to do. Even watching others play, I can feel the harmony between man and machine. All the same, though... it would have been nice to have filters on the DX7 from the get-go.

Q: Actually, digital filters didn’t exist until 1989, when the SY Series was released.

YM: Ah, OK. So that’s why theDX7 didn’t have any.

NN: At NAMM, soon after theDX7 went on sale, I saw a lot of different add-ons and accessories being sold by DIY builders from all over the world. One of them was an analog filter that could be plugged into the back. As you’d imagine, the analog output from the DX7 was just routed to the filter as input. They also had control boards with knobs for all parameters and cases for ROM cartridges.

Q: Was the fact that MIDI appeared around the same time as the DX7 also significant?

NN: The Oberheim OB8 was released the same year as the DX7, and it also had MIDI. So I would always layer the two, with the DX handling the attack and the OB-8 filling out the rest of the tone. Acoustically, they worked really well together.

YK: Yes, the DX7 became pretty popular as a master keyboard.

SH: A DX7 or DX7II was often set up for arrangers and players in the studio because they had such a good keyboard, but they couldn’t output velocity 127, and that caused a lot of problems. Some synths from other makers wouldn’t produce the right sound without that top value, so we used an MEP4 (Note 2) to bump up the MIDI velocity.

Note 2:

An invaluable tool in many studios, the Yamaha MEP4 was a MIDI event processor that could be used to change MIDI channels, Control Change numbers, and other parameters in real time.

Q: What are your thoughts about the distinctive sound of the FM tone generator?

YK: I used a TX802 all the time, and FM was my go-to particularly for electric piano, bass, plucks, and cowbell-type sounds. Back then, I also used a library package called Galaxy to store sounds I made, and I’ve now converted that data so I can play my old sounds on a soft synthesizer that can import DX patches.

SH: I still use a TX816 in the studio. The 12-bit DAC gives it a unique character, but it does require a bit of maintenance. You can often hear a kind of a slurpy noise in the release, but the lower bit rate does give thicker-sounding tones with highs that stand out in the mix. Even the DX7 and DX7II sound different from one another, with the DX7II producing incredibly clear tones. That said, the slightly noisy sounds on the original DX7 do blend well into orchestral mixes.

NN: Do you remember when everyone started using a DX electric piano layered on a real acoustic piano to get the David Foster sound? The DX could also be micro-tuned (Note 3), and that made it really useful when playing with acoustic instruments.

Note 3:

Electronic instruments are generally tuned in equal temperament; however, micro-tuning allows each note (C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, and A#) to be fine tuned separately, providing support for pure major, pure minor, and other temperaments.

Q: It has been said that, when the DX era ended and they were replaced by the new SY Series, the AWM tone generators on those synths had much fewer emblematic sounds than FM. Did you actually use these Yamaha instruments in your work?

NN: I feel that Yamahas were still put to good use for regular stuff. When making music back then, we piled all kinds of synths high on racks and connected them with MIDI to create new sounds. Being able to combine instruments from different companies kind of helped to make the music more multidimensional, and Yamaha synths were also regularly used in this kind of setup.

YM: While the SY Series did replace the DX synths, they also had an FM tone generator on board, and they let you layer tones internally to create sounds that had only previously been possible by MIDI layering of separate FM and PCM synths. I’m pretty sure this made them very useful in the studio.

NN: Incidentally, we Japanese have some kind of psychological aversion to using presets as is (laughs). We also had to at least look as if we were working hard in the studio, so maybe there was a certain amount of preset editing going on in order to seem busy.

Q: Can you remember any standout sounds that you added to songs by the artists you worked with?

NN: The song Densha (Train) by Takako Okamura has a DX7 sequence, and even listening to it now, I don’t think it could be made without FM or possibly even a Yamaha DX. Also, Hikaru Utada’s Give Me a Reason features an FM electric piano. There’s a synthy rhythm loop low in the mix that’s kind of weird, but I really like it, maybe because it still sounds new to me.

YM: For me, it would be the FS1R sound used in Suisei (Comet) by Noriyuki Makihara. As soon as I heard the demo and title, I knew I wanted to use that synth. There’s a kind of an otherworldly quality to the sound I came up with, and I was happy to be able to show off the unique abilities of the synthesizer as an instrument.

YK: There are quite a few, but when it comes to the electric piano, my favorite is Tokyo Sally-chan by Southern All Stars. It’s quite a striking sound and kicks in with a lot of low right from the intro. It comes straight from an FM tone generator and is actually pretty well put together. The pluck sound on What To Do ’Cause I Love You by Taeko Onuki is also FM. I called the patch “Sanukite”, even though, at the time, I had never actually heard the unique sound made by striking the volcanic rock of that name. I just kind of assumed that’s what it would sound like (laughs). We were recording in New York with the guitarist Marc Ribot at the time and he loved the sound. I remember him calling it a real bone-crusher. In terms of bells, the climbing sound in Kyoko Koizumi’s Anata Ni Aete Yokatta (I’m Glad I Met You) was created by compressing layered cowbells and other similar tones from a TX802.

SH: The bell sound in the intro to Garasu no Shonen (Glass Boy) was made by mixing four TX818 layers with a little bit of extra tonal content from a synthesizer made by another company. It has become a very recognizable sound and really gets the crowd going at concerts. For synthesizer bass, it’s become a tradition at our company to blend FM tones with sounds from Sequential Circuits’ Pro-One synth, and you can hear this in songs from TM Network and Tatsuro Yamashita.

Q: When working with your TX816, Shigeaki, do you edit sounds directly on the synth?

SH: I used to use Unisyn for patch editing, but I now have Midi Quest12 running on a Mac. The synthesizer and computer are connected via MIDI In and Out, and they start talking to each other after I press the module select button, so having separate MIDI ports for each module would be very convenient.

Q: Do you know of any ways of using synths that are unique to Japanese music production?

NN: A “pad” is an atmospheric part made up of simple chords, and it can only really be created on a synth. Many producers—particularly during the eighties and nineties—would lay down a pad track at the start of a recording session to help glue the mix together by filling in the spaces between the piano, guitar, and other instruments. There is a tendency in Japanese pop to underpin the melody with strong chords in the backing, and when viewed in this light, the pad becomes the linchpin of the arrangement. Pads from digital synths can, however, stand out a bit too much, so analog synths are often better.

SH: Sometimes a guitarist, for example, can intentionally play notes not in the chord, leaving a gap in the backing that can sound like a mistake, and on occasion, I have been asked to strategically add some synthesizer to make the mix sound whole again. The resulting chord could often sound much cooler than expected.

Q: When creating sounds, have you ever had to put on the hat of arranger or engineer?

YK: What we were asked to do on the synthesizer was often pretty vague—such and such a sound in such and such a place—but we did our best to come up with as many ideas as possible. We usually wanted to try all of them and see what people thought. There were even cases where the sound was replaced after mixdown.

YM: Noriyuki Makihara also does this. When we think the mix is done, he might ask for a different bass-drum sound. Nowadays, we have all of the files for each recording project at our fingertips, so it’s just a case of sending off the right one. It’s actually even more convenient than that, because these days we can shoot off three or more different variations to see which one is preferred.

NN: We only had a maximum of 24 channels on multitrack recorders until the mid-eighties, so synthesizer operators would usually carry their own effects units around with them and record wet. I can remember sometimes being asked by the engineer to turn off the reverb or whatever I had added so he could mix it in. Mostly we did provide complete tracks, though.

SH: Only 16 tracks were available to play with when Tatsuro broke onto the scene, and there was a tendency to record instruments in mono back then, because being economic with limited tracks meant that several could be kept free for multiple vocal takes at the end. Even now, mono is sometimes used for parts like strings. There’s a school of thought that a track definitely won’t work in stereo if it doesn’t work in mono, so even synths often start out as mono recordings and are only switched to stereo if it’s considered necessary later on in the session.

Q: Are hardware synths still being used for recording?

YK: I only use soft synths these days, even for FM.

SH: I think I mentioned that I still use a TX816, and our studio master keyboard is an SY99. I have a DX7II, and an FS1R, and I also use the MONTAGE. My default for electric piano is that DX sound, but when I need a little something extra, I usually go to a MONTAGE. It also comes in useful a lot for drums, bass, and keyboard sounds. We actually have a lot of Montage hardware synths, both for the studio and the stage.

NN: In terms of Yamaha hardware synths, I still use a CS1x. It’s awesome for really silky pads that don’t hog the low end. I’ll have to shut up shop if it ever breaks (laughs).

YM: Back in the day, I sometimes felt more like a moving guy than a programmer, carrying heavy equipment around town and setting it up in a different place every day. So now, the luxury of doing everything in the box seems almost unreal, and people are definitely moving in that direction. I rarely use hardware synths any more myself, but I do go back when finding the right patch is a pain, because it can be much quicker to get the sound I need by twiddling knobs and pressing buttons.

YK: Yeah, with so many presets on today’s soft synths, it’s too easy to get lost in the woods (laughs).

YM: These days, I usually don’t store the sounds I create on hardware synths. I just record the audio and turn off the instrument. For me, tones built from scratch on software synths come out sounding wishy-washy and uninspiring, maybe because I’m used to the higher quality DACs on hardware gear. There’s just something more solid about hardware sounds—they hit the spot. For me, it’s one of the clear benefits of these synths.

Q: What new things would you like the next generation of hardware synths to do?

SH: Could you make the buttons even more intuitive? For example, it would be great if the ones for selecting patches were immediately obvious. Modern synths have far too many, in my opinion, although that does make the DX7 look even more elegant today than we thought at the time. Another thing—I’d love to see buttons that could be locked when not needed. If only the buttons needed for switching sounds could be made active during live performances, that would help to avoid disaster when the wrong one is pressed by mistake.

YK: I record using a CP4 Stage as my master keyboard, and I stick a specially cut-out piece of transparent plastic board over the control panel so nothing gets pressed by mistake. This isn’t done for concerts, though, and recently during a live performance, an entire pad part got played an octave too low because the keyboardist pressed something he shouldn’t have.

NN: We all put sheet music on top of the synthesizer from time to time, right? And when we try to write on it, something gets pressed by mistake. Next thing you hear is “beep, beep, beep” and then cold sweat... (laughs).

YM: I would love a single hardware instrument that can handle all types of sound. I’m not talking about a workstation synthesizer that does everything on hardware—more like a DAW-based system that caters for subtractive, FM, and all other kinds of synthesis. I’m thinking of a tone-generator module rather than a keyboard, but if on-board editing is also going to be supported, a desktop unit would probably be best.

YK: Well, if you’re going to edit sounds, it should definitely have knobs, right?

In Conclusion

We spent three absorbing hours chatting about synthesizers with our guests, although they had so many valuable insights to share that we could certainly have gone on for much longer. It would be impossible to condense everything they had to say into these paragraphs, but there were some clear takeaways. First and foremost, the DX7 and other Yamaha synths have clearly had a major influence on J-Pop. What’s more, the FM tone generators that we introduced in 1983 are still in widespread use today, and incidentally, this is one of the main reasons for our inclusion of an FM-X tone generator on the latest Montage synthesizers. For example, the current Montage M supports the layering approach to sound creation favored in studio production as well as smooth morphing between tones. With luck, we will not have to wait long until the arrival of a new Yamaha synthesizer that seamlessly integrates not only the VL, AN, and FS tone-generation approaches mentioned in the interview, but also all other styles of synthesis developed by Yamaha over the years.

Interviewee Bios

Nobuhiko Nakayama

Nobuhiko Nakayama

After having started his career in the eighties, Nobuhiko Nakayama went on to work as a synthesizer programmer for many leading J-Pop artists such as Hikaru Utada and Ringo Sheena. He also joined Miyuki Nakajima as synthesizer operator on her Utakai Volume 1 tour, and has recently been pushing the boundaries of the modular synthesizer in the live-performance arena through his work with experimental music unit DenshiKaimen and his solo activities.

Yoshinori Kadoya

Yoshinori Kadoya

Upon joining Top Co., Ltd in 1988, Yoshinori Kadoya started his career in music as assistant to company president Takeshi Fujii. The following year, he partnered up with Takeshi Kobayashi and became involved in recording for Taeko Onuki, Southern All Stars, Mr. Children, Kyoko Koizumi, Yosui Inoue, Misato Watanabe, and other household-name artists. He currently programs and operates synths for Keisuke Kuwata and Southern All Stars among others.

Shigeaki Hashimoto

Shigeaki Hashimoto

As synthesizer programmer, Shigeaki Hashimoto has contributed to songs by famous artists such as Tatsuro Yamashita and Mariya Takeuchi. And as a recording engineer, he has most recently mixed all songs on the Tatsuro Yamashita album Softly. He sees his mission as improving the ambience of music all over the world by creating sounds that combine the best of vintage hardware and soft synths.

Yasushi Mohri

Yasushi Mohri

Not only has Yasushi Mohri worked as assistant to the world-famous Ryuichi Sakamoto and contributed to recorded works and concerts by other notable artists such as Noriyuki Makihara, but he has also played a key role as a programmer, synthesizer operator, chorus singer, and percussionist at events such as the world’s largest anime song music festival, Animelo Summer Live. In recent years, he formed the group Yasushi Mohri & The Best and posts covers of famous anime songs, performed without the use of any computers, to the band’s YouTube channel.